Dave of Old Edgefield

Still thinking about The Metropolitan Museum of Art's Exhibit: "Hear Me Now: The Black Potters of Old Edgefield, South Carolina"

The “Hear Me Now” exhibit at the Metropolitan Museum of Modern Art in New York City is displayed and presented as an amalgamation and dialogue between the work of African-American potters in the 19th-century American South and contemporary artistic responses to those works; the exhibition contains about fifty works from Old Edgefield District, South Carolina, dating from the antebellum period before the start of the American Civil War, and since I saw it for a second time at the start of the year this January, Dave Drake’s work and words have since, and still, stay stuck in my mind.

Of the original Antebellum works from Old Edgefield in the “Hear Me Now” exhibit, many came from that noted “enslaved and ‘literate’ poet and potter” by the name of David Drake. From Drake’s monumental works of pottery, historians, as well as the general audience from The MET, were able to get a glimpse into not only what it was like for enslaved laborers during the antebellum period but also it provides a look at what kind of person David Drake was, how he chose to react to his cruel world, and how his self-expression through his pottery and poetry can be seen as a personal act of rebellion and resistance in this time period of bondage. For God’s sake, it was illegal for enslaved men and women to even have the ability to know how to read and write.

Before the abolition of slavery in the United States prior to the American Civil War, the pottery industry and manufactory in the town of Old Edgefield, South Carolina, was a significant contributor to the local economy. Pottery was a major source of income for the town, and the enslaved African-American population was the most significant part of the industry and, in tandem, the whole town’s labor force. Enslaved persons were used throughout the town's pottery industry to dig clay, form the vessels, and fire the pottery in kilns, and for certain craftsmen, as well as working on the potting itself.

The potters of Old Edgefield, for their economic class and the condition of their treatment in the town nonetheless, possessed a truly unique set of skills that ended up being essential to the production of high-quality pottery. They had to be able to identify and select the right clays for a particular piece, as well as to mix and apply the clay in the desired shapes. Potters also had to have knowledge of kiln firing to ensure that the pieces were strong enough to last.

The pottery trade in Old Edgefield was a major source of income for the town and especially its major slaveholders. Pottery production was a profitable business, and many slaveholders saw it as a way to make extra money, with many slaveholders designating certain members of their enslaved labor force solely into the potter industry. The pottery items made by slaves in Old Edgefield were sold throughout the South and across the country. However successful the pottery industry was in Old Edgefield, it was built off of the backs of the enslaved African American population; the same people who contributed most to the labor forces received none of the economic benefits and value their work created.

We don't know much about the large numbers of people who were making these pots and jars at the time; however, through the poetry and inscriptions on some of the most ornate and immaculately constructed pots of those discovered, one man wrote on his work, despite it being a crime in his time, and because of that we do know of one of the most prolific of these potters, and he was a man by the name of David Drake, a man signed Dave.

Dave was a potter who lived in Edgefield County, South Carolina, during the nineteenth century. He was enslaved in 1820 and was owned and enslaved by a prominent Edgefield family tycoon of potters, the Landrum Family.

The elite of the region highly sought after Drake’s works, and due to him being such a skilled potter, he was often allowed to keep some of his works as payment to later sell on his own. A New York Times article on Dave’s work cites Jill Beute Koverman, a curator assistant at the Atlanta History Center, that Dave in his life was responsible for the creation and craft of more than forty thousand pieces over his lifetime. There was a reason Dave’s pottery was so well sought after, these tens of thousands of pieces were not made in vain or with a lack of care; these jars, pots, vases, and other ceramic objects were masterfully done often to a massive scale, crafted with tens of pounds of clay, with

“his largest works, which were 29 inches high and held up to 40 gallons, must have required awesome strength.'' (Reif)

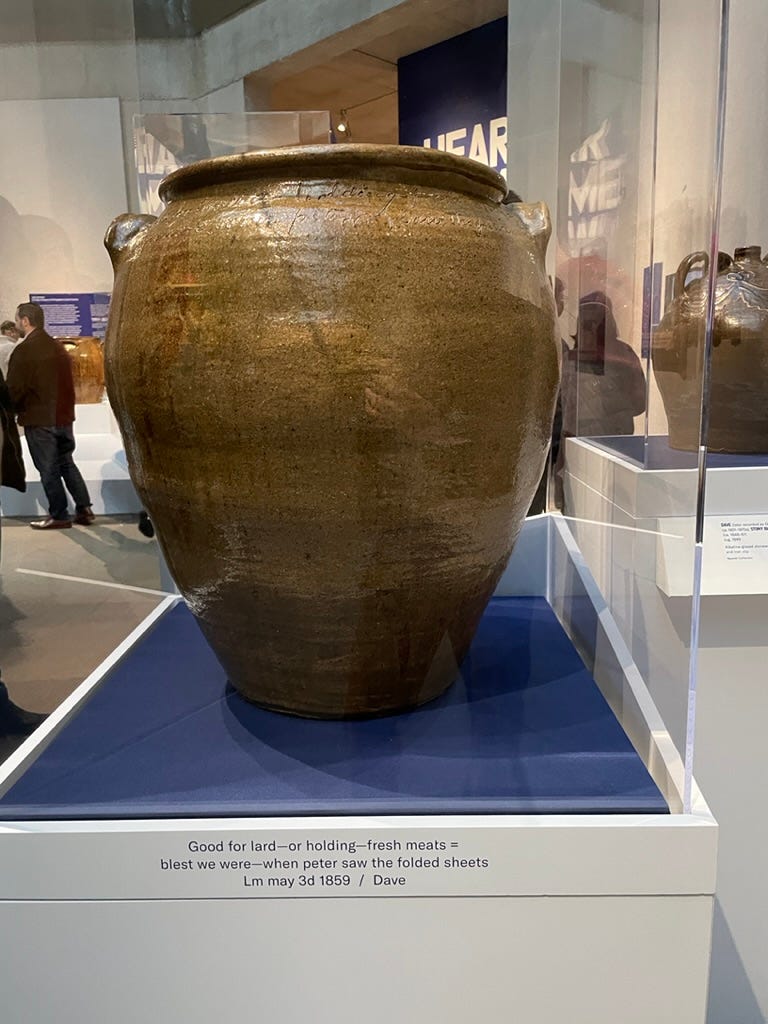

These pots were made to such high quality and thickness that they were even used for storing meats, with the exteriors and craft of Dave’s pottery often being compared by historians to the medieval ash-glazed pots produced at Shigaraki, Japan. For someone with likely minimal pottery training, it's remarkable that Dave, through his work, was able to eclipse the works of people who trained years, if not decades, to do work akin to Daves.

However impressive the work of Dave Drake may be on a physical material level, it is impossible to ignore the poetry and messages and the sheer fact that they’re there in the first place. Despite the danger, Dave would write prominently on the exterior of his pottery, with his written messages not only presenting profound statements on his “current” economic and social condition but also presenting some interesting insights into his personal life that can help modern-day audiences understand the conditions of the artist Dave.

From what we know of Dave, he was prone to write on as many of the pots as he could, whether these be quotes, aphorisms, or pieces of poetry, though many of them were addressed to those whom his pottery was made for.

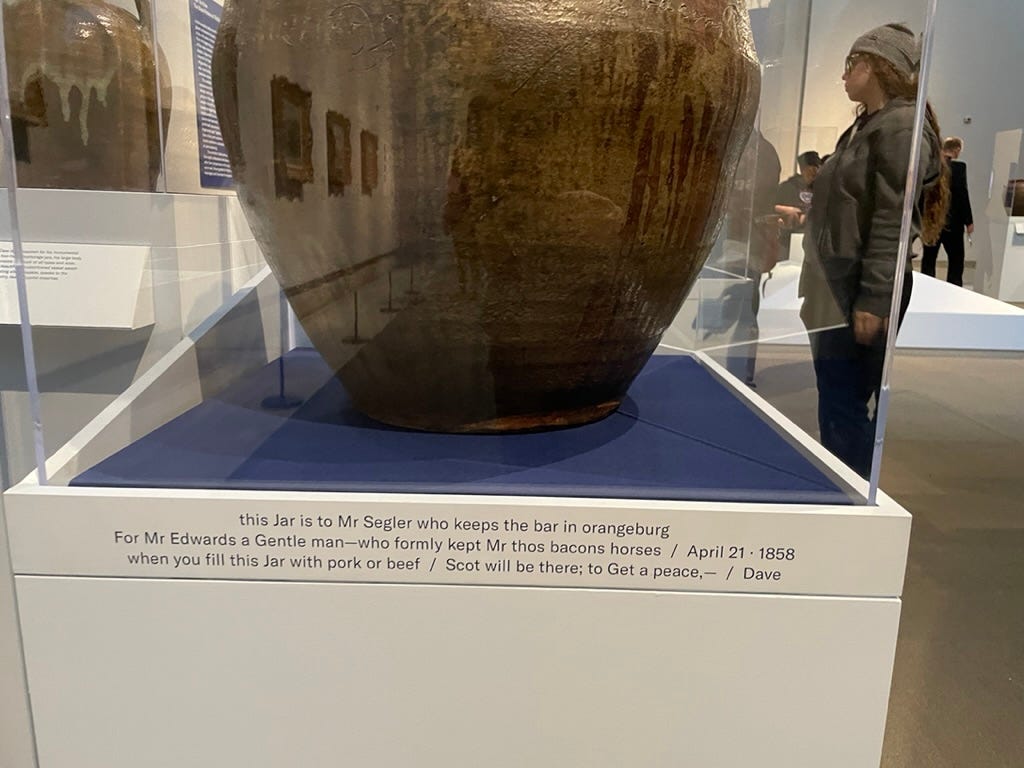

One pot that gives us a glimpse into the daily lives of Old Edgefield is a pot dating to 1858, seemingly addressed and made for a Mr. Segler:

“This Jar is to Mr Segler who keeps the bar in Orangeburg For Mr Edwards a Gentle man-who formly kept Mr thos bacon's horses / April 21 • 1858 when you fill this Jar with pork or beef / Scot will be there; to Get a peace’, -/ Dave”.

This quote can infer that Dave was skilled enough to be personally commissioned to make pots for a man such as Mr. Segler, but more interestingly, this also shows us that Dave was active in communities and towns himself, such as in places like the aforementioned Orangeburg, and reaffirms historian’s assumptions that he was personally contracted for his work throughout the South Atlantic States.

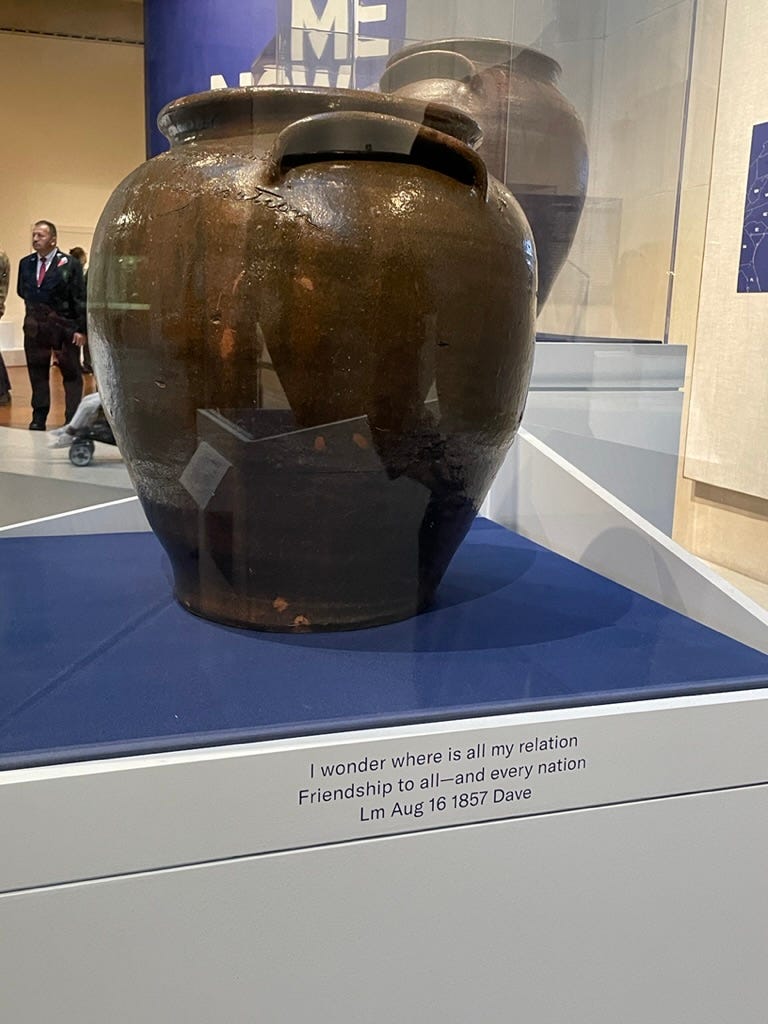

One of the most striking pieces of writings that have been discovered (displayed above) and preserved was not for the description of who the given pot was for, like many others, but instead, this pot was preserved due to an expression of the yearning Dave may have felt during his life in bondage:

“‘I wonder where is all my relation / Friendship to all-and every nation’ Lm Aug 16, 1857 -Dave”.

This aphorism from Dave exemplifies the yearning and the pain felt by the majority of the African diaspora in the Americas in his time, but despite that, he calls out for peace. The enslaved population in the United States, as well as all of the African peoples displaced from the global slave trade in large part, were stripped of their culture, their heritage, and their families. Like many other unfortunate people in his time, Dave was most likely stripped of any connection to his family, heritage, and culture he may or may not have lineage to. Still, despite all of that, Dave calls on a message that incites peace and friendship amongst all peoples. This was believed to be a primary wish in that short, impactful aphorism. The context that Dave’s pot was made In 1857 in antebellum South Carolina is especially notable when discussing these works and especially in the case of his more political works. At that time in South Carolina, in which Dave was a potter and when he was writing his poems, his aphorisms, and his messages across the sides of his works of pottery, again, it was illegal for an enslaved person to know how to read or write. Dave did not write any of his messages or sign his name silently in small text to the side; instead, he wrote prominently and in extensive, easy-to-see writing across vast segments of his pots and jars. It is the fact that he wrote and added to his work so prominently, even when it was criminal to do, that exemplifies Dave’s incredible act of rebellion through his art.

Including the “Hear Me Now” exhibit featured in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the pottery that Dave created has been preserved and is now on display in a number of museums around the country. His work reveals a great deal about how enslaved potters were able to transcend their status of enslavement through their pottery work and self-expression. Dave’s pottery was a way for him to resist the oppression of slavery and to express his African heritage through his mastery of pottery and through his rebellion through his use of language. Dave’s work also reveals the creativity and skill of the potters of Old Edgefield and how they were able to produce beautiful and unique pieces of pottery despite their material conditions in an unjust, cruel, and vile economic system they were subjugated to.

Dave Drake’s pottery provides an important window into the lives of enslaved people in not just Old Edgefield but all enslaved members of the African diaspora in the South. His work is a testament to the resilience and creativity of the people who lived in bondage, and it serves as a reminder of the importance of art and craftsmanship in the lives of oppressed people to foster ideas and sentiments of liberation through mediums of art. The pottery produced in Old Edgefield reveals how these enslaved potters were able to transcend their status of enslavement through resistance and self-expression. Dave’s work is a reminder of the power and value of art, creativity, and craftsmanship. To me, Dave’s work serves as a reminder of the importance of honoring the contributions of all people, regardless of their race or status, in all aspects of society, and it made for a really cool exhibit that I really hope the MET brings back.

Posted an embedded link to it earlier in the article, but I’m gonna post it again because I do really and highly recommend checking out the video from the MET’s official YouTube channel made jointly with the opening of the exhibit.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=C0g3pC4cgu0&t=9s&ab_channel=TheMet

Very interesting article - I hope to see Dave’s work someday...art is certainly a pathway to one’s soul.