Landlords Kinda Suck: Gentrification and Housing Policy in Urban America

There are more renters than there are leeches, better solutions and a better world is possible

66% of residents in New York City are renters, and across every major metropolitan urban center throughout the United States has a majority of non-homeowning residents. Boston, with 65% of its residents as renters, Los Angeles at 70%, and Chicago at 66% renting is just the fact of life for middle and working-class urban Americans. Now the “American Dream” of home ownership many suburban and rural Americans achieve just isn’t a reality for the majority of American urbanites. Urban renters face a wide variety of problems, from rising rents and cost of living to inflation to displacement, but in the last decade, the often controversial discussion around gentrification has become top of mind in most discussions across urban America.

Tensions surrounding the topic of gentrification are high in urban America, and it continues as a hot-button issue. With it comes hostile discussions surrounding the dichotomy between new tenant gentrifiers and original residents at risk of displacement. Gentrification is often described as the process of changing the character of a neighborhood through the influx of more affluent residents and businesses while displacing original residents with less economic capital. When new tenants with higher amounts of economic capital and the ability and willingness to pay more for rent and amenities move into lower-income areas in urban centers, the cost of living increases tremendously, making it hard for the original residents to afford to live in the places they grew up. However, almost all discussion surrounding gentrification in urban America centers on the dichotomy and relationship between new tenants and original residents, ultimately disregarding a predatory third party that benefits and profits most from these two groups of renters and the process of gentrification. All renters have to pay their rent to someone, and that predatory third party are the landlords.

No average American urbanite has the financial resources and capital to buy their own home or building, and the social housing in the U.S. is laughable in comparison to those in China or in the European Social Democracies, which makes renting and interacting with the landowning class a near necessity for those who wish to live in the urban capitals of the U.S. America’s housing runs under a market system where housing is viewed as a commodity in which landlords who have the wealth to do so hold the vast majority of property in most urban centers, landlords have an economic incentive to raise rents and increase profits to meet market demand, and cater to tenants who have the ability and capital to pay more. Landlords exacerbate the problems of gentrification, and they not only will make these problems worse for original residents, but without sufficient rent control and housing alternatives, they are incentivized to do so.

When we think of landlords in the colloquial sense, the average American usually pictures noncommercial housing firms, mom-and-pop shops that own one or two buildings, and individual and independent “slumlords” raising rents. However, in the last decade, the housing market has drastically corporatized and centralized into the hands of predominantly large private equity groups and hedge funds. In the city of Atlanta, according to a 2019 Atlantic article, “between 2011 and 2017, some of the world’s largest private-equity groups and hedge funds, as well as other large investors, spent a combined $36 billion on more than 200,000 homes in ailing markets across the country. In one Atlanta zip code, they bought almost 90 percent of the 7,500 homes sold between January 2011 and June 2012” (Semuels). The monopolization of housing in major cities makes the issue of commodification even worse as the disconnected; often, multinational investment firms are even less concerned about the lives of tenants than small property-owning landlords. A study from the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta found that corporate landlords were “18% more likely to file evictions than small landlords”(Raymond). Even more concerning is that some of the largest corporate landowning firms discussed in the study filed eviction notices on up to a third of all their total properties within a year. The quote by German writer Erich Maria Remarque, though dramatic, illustrates this trend well: “The death of one man is just a death, the death of two millions is a statistic.” At the scale of the corporate landlord that will probably never meet or ever interact with their thousands, if not tens of thousands of tenants, those landlords can no longer view the student, the single mother, the businessman, and the artist as anything other than a “statistic.”

Under a market system where housing is viewed as a commodity in which landlords hold the vast majority of property in most urban centers, landlords have an economic incentive to raise rents and increase profits to meet market demand and cater to tenants who have the ability and capital to pay more; however, this process of continued profit accumulation stops when the amount of profit offered by a given building is capped, and that cap and solution in many cases is rent control. Rent control is most commonly defined as government control and regulation of the amounts that landlords can charge for rented housing. Like all other government-regulated controls on the prices of commodities and expenditures, rent control comes in the form of a series of laws that place “rent ceilings” , or maximum prices that landlords are able to legally charge tenants. A 2019 Stanford study found that “rent control increased the probability a renter stayed at their address by close to 20 percent.” (Diamond et. al). The price cap may be what's implemented on landlords, however, the goal of these policies are to protect tenants that can’t afford steep rent increases from their landlords, as well as protecting those same tenants from economic displacement from their homes. Displacement is driven by an unrelenting and unregulated market looking for profit, and with that search for profit and further wealth accumulation means rising rents. A 2021 article by The Hill argues that “by curbing excessive rent hikes and preventing retaliatory or unjust eviction, rent control mitigates the power imbalance between tenants and landlords, advances overall neighborhood stability, and prevents an eviction crisis as our cities become more expensive places to live” (Weaver). With this, people that can afford to stay in their homes have security and reassurance that they are able to stay in their homes without the fear of displacement, and it also, by law, negates the market incentive for landlords to evict original residents in favor of new tenants with higher financial capital.

Rent control is good, but it's not “a” or” the” final solution to the major issues that face the core issues of displacement and gentrification. With regard to rent control or any “price ceiling” under a market system, if you set a maximum price for a good below what the market price would be, you lower the incentive for landowning firms and developers to build and rent landed property for tenants. It is the scarcity of housing that gives it value under a market system, and it is the scarcity that influences and empowers those that have land over those who don’t, and though rent control does help the issues of gentrification and displacement, it does nothing to make housing less scarce. Ultimately, rent control policies do help people with the affirmations Stanford study citing that “rent control increased the probability a renter stayed at their address by close to 20 percent.” (Diamond et al.). However, with landlords still controlling the commodity of housing and what groups the scarce resource of housing goes to, Rent control only offers a bandage solution to the broader issue of the commodification of housing. It is for these reasons that the introduction of public housing initiatives, developments, and legislation akin to the “Vienna model” of housing may offer a solution to the commodification issue.

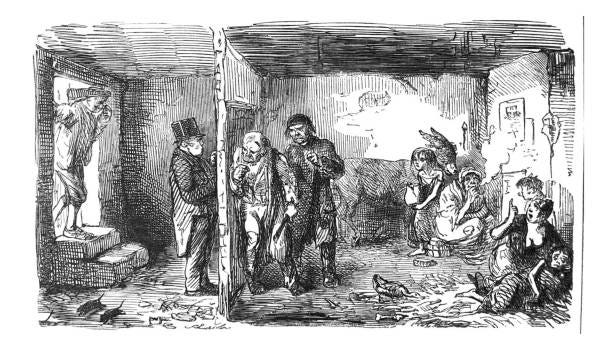

Before a discussion as to what housing alternatives removed from the influence of landlords looks like, it is important to understand the history of where the landlord class originates as well as the history of landed property itself. Landlordism and “renting” of property have historically existed as an economic mode of capital accumulation even before the rise and establishment of capitalism.

(Get ready I’m about to be annoying and quote Marx, but he’s always right about this sort of thing)

The origins of landed property find its origins in the structure of feudalism, defined as an economic system where land was the basis of all economic and political power before capital and the extraction of surplus labor. This became the key economic driver in the transition from feudalism to mercantile capitalism. According to German philosopher and economist Karl Marx, in his work, Das Kapital, Volume III, surplus value is defined as the excess of value produced by the labor of workers over the wages they were paid. Marx’s description of surplus value is based on a model of economics and production under capitalism; however, under feudalism, “rent” and surplus value were identical. Under feudalism, all value and labor produced by feudal peasants were directly expressed by the “rent,” or the ability for a feudal peasant to exist on a plot of land. In the hundreds of years following the transition from feudalism to capitalism, the only thing that has changed with respect to rent is what economic class the value of rent is given to. With this, the primary distinction of capitalism with respect to feudalism is defined by the separation of the economic classes to which workers/peasants give their labor and rent, as most renters, in order to maintain, keep, and gain access to the shelter must set aside a portion of their accumulated capital into their rent. “The transformation of rent in kind into money rent,” writes Marx, “that takes place at first sporadically, then on a more or less national scale, presupposes an already more significant development of trade, urban industry, commodity production in general and therefore monetary circulation.” However, workers under capitalism do now have the ability to spend their earned capital on other commodities separated from rent and the landlord/feudal lord. The average working-class urban renter may give their labor to others besides their landlord to gain capital, however, to gain the privilege of shelter; a renter must always have enough to pay.

There is no doubt that the introduction of a stronger rent control policy, the introduction of subsidies for public housing, and or the abolishment of landlords as a class would obviously be economically disadvantageous for landlords. The case as to why we should disregard the whims of the landlord class is not because the people who are landlords are individually and uniquely evil people. Instead, the case against landlords revolves around the fact that they don’t create value. Many may argue that “If landlords don’t create value,” then why does anybody rent? Do landlords not provide a service of selling a living space for those that do not have the capital to own a property outright? The answer to both of these questions is no. Scottish Economist Adam Smith states that “as soon as the land of any country has all become private property, the landlords, like all other men, love to reap where they never sowed, and demand a rent even for its natural produce.” From the landlord, there is no new value being created, as all value they offer already existed and continues to exist before and after the landlord. The “service” that landlords provide by “offering” shelter is the opposite of reality. Landlording is the denial of access to already existing shelters. In that, the landlord is simply using property relations and exorbitant amounts of capital to buy the licensing to restrict access to the human necessity of shelter to extract a person’s wealth to a product that is otherwise available without the existence of a landlord.

Public housing is most commonly defined as a form of housing in which the property is owned, controlled, and funded by the local or central government. In a 2020 NPR article, author Ally Schwitzer wrote about how European-Style public housing projects akin to the Vienna model could help solve the housing affordability crisis amongst renters in the urban United States. In the U.S., the concept of public housing comes with very loaded connotations. Public housing in the United States was primarily an initiative pushed following the end of the Second World War. In Schwitzer's article, she interviewed Saoirse Gowan, a senior policy associate with the left-leaning Democracy Collaborative, stating that public housing, or “projects,” in the United States have “been reserved for poor residents, typically black Americans barred from economic opportunity. Owned and operated by governments, disproportionately located in high-poverty areas and exclusively available to the neediest occupants, public housing has never had a working financial model.” Public housing's implementation in the United States of America was seen as a last-ditch resort to stop widespread homelessness among already impoverished communities, many of whom did not receive the same social and financial benefits offered to white and middle-class Americans following the "New Deal era. Public housing in the United States was, upon creation was nearly immediately disincentivized, with Gowan stating that “Public housing in the United States was designed to fail.’ ‘it was designed to be segregated, it was designed to be low-quality” (Schweitzer). In Vienna, Austria, however, the government's “social housing” public housing policy did not suffer the same fate. Compared to public housing projects in the United States, in Vienna, social housing serves a different purpose of simply providing housing to the broader public, and according to the London School of Economics, “social housing accounts for an estimated 40% of the housing stock in Vienna.” This 40% of the population, however, is not solely in the lower class of the city, this broadly high-quality housing stabilized by the government is open completely to the whole public across varying incomes, ages, and populations within the city. Gowan herself, living in social housing, stated, “It's something that even a relatively well-off person would say, ‘This is good enough for me; I'm happy here'’” (Schweitzer). Social housing is also typically placed in desirable areas within Vienna as well as required to meet the same architectural and quality standards as any other private building in the city. Higher-income tenants within social pay the market rate rent for an area, subsidizing rents for low-income residents, with half of all social housing units required to house those making under 53,225 EUR (58,980 USD). On the topic of the European nation’s social housing policy a 2013 article in the US-based Governing magazine noted: “The Viennese have decided that housing is a human right so important that it shouldn't be left up to the free market” (Holeywell). Housing policy like that in Vienna is found across the world in places like Hong Kong, Singapore, and Barcelona, all of which are seeing success amongst renting populations with high standards of living, notably all without highly fluctuating rent costs that drive displacement, and most principally all without the involvement of landlords.

According to UC Berkeley’s Urban Displacement Project across the country, “41% of all households in our 53 metro study area (26.9 million) live in neighborhoods where there is a high level of vulnerability to eviction or displacement” (Chapple). These 41% of households represent thousands of families, students, couples, and people just trying to scrape by with an economic system that not only disincentivizes their housing but this system, all the same disincentivizes the renters, the people themselves. The process of gentrification drives displacement, and in the United States, gentrification has an extremely hot-button issue. The debate surrounding gentrification has pitted the “tribes” of “original residents” and “new tenants” against each other, but this debate and conflict between manufactured factions won’t ever solve the systematic issues with American Housing policy and the commodification of housing. There are existing housing legislative efforts across the world, in nations with economies per-capita much smaller than the United States, that actively work to alleviate the financial pains and housing insecurity that their citizens face; these policies are capable of being implemented in the U.S. Will our government be pressured to make housing policy work to help make the majority of urban Americans’ lives easier, or will our housing policy continue to cater to the pockets of the small leeching landlord class?

Works Cited:

Cea Weaver, opinion contributor. “There's No Denying the Data: Rent Control Works.” The Hill, The Hill, 24 Sep. 2021, https://thehill.com/opinion/finance/573841-theres-no-denying-the-data-rent-control-works/.

Chapple, K, et al. “Housing Precarity Risk Model.” Housing Precarity Risk Model, UC Berkeley's Urban Displacement Project, https://www.urbandisplacement.org/maps/housing-precarity-risk-model/.

Demsas, Jerusalem. “I Changed My Mind on Rent Control.” Vox, Vox, 2 Dec. 2021, https://www.vox.com/22789296/housing-crisis-rent-relief-control-supply.

Diamond, McQuade, Qian. “The Effects of Rent Control Expansion on Tenants, Landlords, and Inequality: Evidence from San Francisco.” American Economic Review, vol. 109, no. 9, 2019, pp. 3365–3394., https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20181289.

Holeywell, Ryan. “Vienna Has Figured out How to House Its Population—from Poor to Solidly Middle Class—in Luxurious, Low-Rent Apartments.” Governing, Feb. 2013, pp. 28–30.

Immergluck, Dan, et al. "Evictions, large owners, and serial filings: Findings from Atlanta." Housing Studies 35.5 (2020): 903-924.

Marx, Karl. Das Kapital. Edited by Friedrich Engels, Regnery Publishing, 1996.

Raymond, Elora L and Duckworth, Richard and Miller, Benjamin and Lucas, Michael and Pokharel, Shiraj, Corporate Landlords, Institutional Investors, and Displacement: Eviction Rates in Single Family Rentals (2016-12-01). FRB Atlanta Community and Economic Development Discussion Paper No. 2016-4, Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2893552

Scanlon, Kathleen, and Christine ME Whitehead. Social Housing in Europe II: A Review of Policies and Outcomes. LSE London, London School of Economics and Political Science, 2008.

Schubach, Alanna. “Stop Blaming the Hipsters: Here's How Gentrification Really Happens (and What You Can Do About It).” Brick Underground, Brick Underground, 15 Feb. 2018, https://www.brickunderground.com/rent/what-causes-gentrification-nyc.

Schweitzer, Ally. “How European-Style Public Housing Could Help Solve the Affordability Crisis.” NPR, NPR, 25 Feb. 2020, https://www.npr.org/local/305/2020/02/25/809315455/how-european-style-public-housing-could-help-solve-the-affordability-crisis.

Semuels, Alana. “When Wall Street Is Your Landlord.” The Atlantic, Atlantic Media Company, 8 Apr. 2019, https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2019/02/single-family-landlords-wall-street/582394/.

Shuli, Redi. “Gentrification and Landlord Harassment.” Spring 2018 Shaping the Future of New York City, 15 Mar. 2018, https://eportfolios.macaulay.cuny.edu/alonso2018/2018/03/14/gentrification-and-landlord-harassment/.

Smith, Adam. Wealth of Nations. Classic House Books, 2009. [Original source: https://studycrumb.com/alphabetizer]