What’s the Deal With the City’s Budget Crisis

The best long summary I can give on the the wealth tax, the property tax, and the four people who'll decide which one we're paying

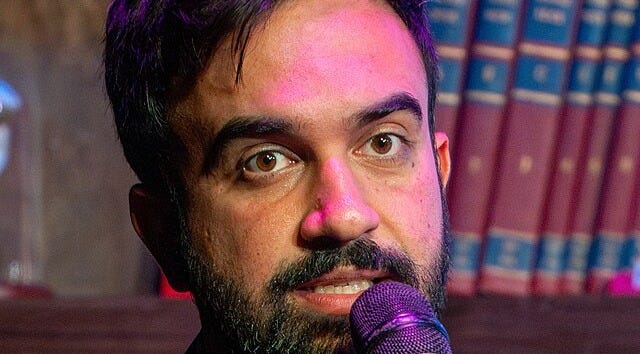

New York City Mayor Zohran Mamdani says the city is in a budget crisis, and he’s giving Albany and the city at large an ultimatum, which I think is getting indirectly, deliberately obfuscated.

I’ve been non-stop listening to politicians and reporters talk about this budget crisis, how to solve it, if it’s a crisis to begin with, and whatever. I’ve been bemoaning trying to do any amount of audio editing for a story for my job that I know has to ignore saying the numbers aloud (like we’re supposed to), so I thought it would be nice to dust off this website and try to explain this as best I can, so all of this budgetary anguish in my head from the last two days doesn’t go to waste.

In his first preliminary budget address at City Hall on February 17th for the 2027 budget (I’ll just put the whole video above here), Mamdani told reporters that the city faces a five-point-four-billion-dollar deficit over two years and, by law, unlike the state and federal governments, the city budget must be balanced (due to the city's fiscal crisis in 1975 to 1975). Mamdani laid out two paths to rectify this issue. His preferred option is for the state to raise state income taxes on New Yorkers earning more than $1 million a year by about 2%, and the alternative, what he called the “most harmful path,” is a nine-and-a-half percent property tax hike at the city level.

Behind that binary, there are four main political actors who are staking out different positions, and the gap between them will, more or less, define who ultimately ends up picking up the tab.

On a more blunt level, Mamdani argues that “we” (the New York State Government) need to tax the rich, or everyone pays (via property taxes, which will also trickle down to tenants via landlords). According to the mayor’s official budget release, the city identified a pattern of underbudgeting in essential services, including rental assistance, shelter operations, and special education, that widened projected gaps to roughly $12 billion across two fiscal years. After applying savings (and essentially doing some austerity), updated revenue projections, and the currently agreed-upon 1.5 billion in new state funding from Governor Hochul, the remaining budget gap still stands at 5.4 billion.

Mamdani said, in remarks during his February 17th address that: “We remain firmly in a budget crisis. It is a crisis that we can and will overcome. Still, we cannot do so without either significant structural changes in Albany, or the painful decision [property taxes] of last resort.”

Unlike what many from the New York Post, FOX, the radio guys at WABC, and whoever else can claim, during the press conference (which I actually did watch), Mamdani made it really clear that this was not his first choice. As reported by the New York Times, Mamdani said, “The second path is painful. We will continue to work with Albany to avoid it,” Which he has continued to stress.

Mamdani was not hiding who the property tax would hurt: “property taxes would be raised by 9.5%. This would effectively be a tax on working- and middle-class New Yorkers who have a median income of $122,000.”

Speaking to reporters afterward, Mamdani told the guys from Hell Gate that his administration had “exhausted nearly every option” and that the wealth tax is “not only the fairest course, but also the most sustainable course.”

Here’s more or less what the property tax hike would look like:

The proposed 9.5 percent increase would affect more than three million single-family homes, co-ops, and condos, as well as over 100,000 commercial buildings across the city, according to the New York Times. According to the mayor’s official release, though, the hike would generate 3.7 billion dollars in fiscal year 2027. The Citizens Budget Commission estimated that this would cost a typical homeowner about 700 dollars more per year. For landlords, particularly those operating in rent-stabilized buildings, the costs would likely be passed on to tenants in market-rate apartments; rent-stabilized tenants are somewhat shielded since stabilization caps how much of the cost can be passed through. Still, for the rest of us in market-rate units(me), it’s bad news.

The city hasn’t seen a property tax rate increase since former Mayor Michael Bloomberg, who raised rates after 9/11 and again during the Great Recession. As THE CITY noted, the effective rate has remained the same since then.

In addition to all of this, Mamdani would also draw on nearly 980 million dollars from the city’s “Rainy Day Fund,” and 229 million dollars from the Retiree Health Benefits Trust, which is a move that would leave the city vulnerable to future downturns (and I doubt the retirees would be happy).

As for Mamdani’s preferred option, here’s what the wealth tax would more or less look like:

This is the option Mamdani says is fairer and more sustainable. Still, it requires the state legislature and especially Governor Hochul to act, because New York City cannot raise its own income taxes without Albany’s authorization.

At the annual “Tin Cup Day” hearing last week (the annual hearing where the Mayor begs the state for money), Mamdani laid out some specifics before Tuesday. As reported by Newsweek, he reiterated to state lawmakers, “I believe the wealthiest individuals and most profitable corporations should contribute a little more so that everyone can live lives of dignity. That’s why, along with raising the corporate tax, I’m asking for a 2 percent personal income tax increase on the most affluent New Yorkers.”

The “Mamdani preferred” proposal has two components:

The first is a 2 percentage point increase in the personal income tax on New York City residents earning more than a million dollars a year. During Tin Cup Day, Mamdani said that “someone earning a million dollars a year can afford to contribute $20,000 more.” There are roughly 380,000 millionaires living in New York City, which is about 1 percent of the city’s population, and these same people already pay about 40 percent of the city’s income taxes, according to the Citizens Budget Commission.

The second component Mamdani is pushing for is a 4-percentage-point increase in the corporate tax rate on large, profitable corporations. During his campaign, Mamdani’s team estimated that the corporate hike would raise about 5 billion dollars annually, and the income tax increase would raise about 4 billion dollars, for a combined total of about 9 billion dollars. At the Albany hearing, Mamdani said the income tax alone would resolve “nearly half” the city’s deficit.

Mamdani also argued the tax increase would be offset by federal tax cuts. He cites a Fiscal Policy Institute report, in saying that the cuts in President Trump’s One Big Beautiful Bill Act would save New York millionaires more than 12 billion dollars in federal taxes each year, which is an average of about $129,600 per taxpayer (in this high-income bracket). In other words, Mamdani is saying that even with these state-level increases, the wealthy would still pay less per year than they spent in 2025.

Of course, conservative (adjacent) groups have pushed back on this, including the libertarian Cato Institute, which estimated in a report that the corporate side would raise closer to 3.8 billion(ish), and warned that a city-specific income tax could drive high earners to Long Island, Westchester, or out of state entirely, though I’m editorializing here, but don’t think this is something the Mamdani camp would believe, or care about too much to put too heavily in their calculation.

Governor Kathy Hochul has been the more immovable obstacle in this whole situation. She has repeatedly pledged not to raise taxes in 2026, and she holds veto power over any income tax increase that comes through Mamdani’s numerous allies in Albany.

At a separate event from Mamdani also on the 17th, Hochul downplayed his property tax threat. As reported by THE CITY, she told reporters she did not “think a property tax increase is necessary.” And according to reporting from NBC New York, the governor suggested Mamdani should look at where adjustments can be made in current spending and avoid “taxing for the sake of taxing” (I’ll get to this later with Speaker Menin).

The New York Times and Hell Gate both reported that Hochul said the mayor has until the summer to work out the real expenses, and that putting [his] options on the table “does not mean that’s the final resolution.”

But Hochul has been folding a bit and steering money toward the city. On Monday, February 16th, the day before the Mamdani budget(and ultimatum) was released, she announced the aforementioned 1.5 billion in additional state funding, including more than 500 million in recurring dollars. This brought the projected deficit down from 7 billion to 5.4 billion, which is good but obviously not enough.

Compared to Mamdani, Hochul is a pro-business moderate Democrat running for re-election (with his endorsement, lmao), and she has to balance downstate progressive priorities against the suburban and upstate voters who already resent how much state revenue flows to the city. Mamdani himself told Albany lawmakers, as reported by Newsweek, that “New York City contributes 54.5 percent of state revenue but only receives 40.5 percent back,” which I still don’t think Hochul can completely ignore.

Despite the ideological gap, Mamdani and Hochul have been unusually close allies compared to what I would’ve assumed a couple of months ago. As the New York Times reported, the mayor, since endorsing Hochul for re-election, told allies he would likely skip a “Tax the Rich” rally planned for February 25th in Albany. So this isn’t necessarily a scorched-earth fight (yet), even though I think there is an argument among DSA/WFP-adjacent groups that it should be. Instead, it’s played out, as of now, as a very public negotiation between people who do need each other.

City Comptroller Mark Levine has staked out a position that validates Mamdani’s diagnosis more than Hochul’s but still rejects Mamdani’s proposed treatment.

In an official statement released on February 17th, following Mamdani’s presser, Levine said Mamdani’s budget “honestly and transparently lays out the scale of our challenges” and praised the end of underbudgeting. He described the city in the presser as being “under the greatest fiscal strain since the Great Recession.”

But he warned that the proposed fix would be harmful. From the same statement: “To rely on a property tax increase and a significant draw-down of reserves to close our gap would have dire consequences.”

In an interview Levine did with NY1 after a closed-door briefing with Mamdani, Levine was more specific in that “raising property taxes would be no one’s preferred option, partly because the system is so flawed, riddled with inequality. It’s essentially a regressive tax as it’s currently structured, hitting homeowners and communities of color much more than it hits homeowners in wealthier areas.”

He also cautioned against raiding reserves like the rainy-day fund during a period of economic growth. He warned it would leave the city vulnerable to future turbulence issues. Levine’s alternative is that “We need to find greater efficiencies and savings across New York City government and reconfigure programs that are growing at an unsustainable rate.” He also said the city “undoubtedly” needs more help from Albany, but stopped short of explicitly endorsing the “Mamdani” wealth tax.

THE CITY reported that Levine called what Mamdani put on the table “a pretty extreme option” that also relies on “pretty aggressive revenue projections.” His office will release its own full fiscal analysis on March 11th, so let’s wait and see if his tune changes

City Council Speaker Julie Menin may matter most in this whole debacle because the Council has final say over the city budget. And she’s carving out a position that neither fully aligns with the mayor nor with the austerity crowd.

In a joint statement with Finance Chair Linda Lee, released the day of the budget, Menin said a property tax increase “should not be on the table whatsoever.” She also said the Council believes there are “additional areas of savings and revenue that deserve careful scrutiny before increasing the burden on small property owners and neighborhood small businesses.”

But in a radio appearance on the conservative Sid Rosenberg show on WABC on February 18th(why did she say this here??????), Menin explicitly opposed both the property tax hike and cuts to essential services. Instead, she pointed to what she sees as “clear areas of waste.”

Her main target for cuts is public sector and retiree healthcare costs. She said on Sid Rosenberg(again, why here?) that the city now spends close to 11 billion dollars a year, which is nearly 10 percent of the entire budget, on public-sector and retiree healthcare, a figure that was 6 billion just five years ago, which she called “unsustainable.”

Menin said the healthcare accountability office she created through legislation two years ago, before she was speaker, could save an estimated two billion dollars annually by leveraging the city’s purchasing power to renegotiate hospital prices. She gave an example about how a C-section costs $55,000 at one New York City hospital and $17,000 at another for the same procedure.

She also went after no-bid contracts: “For years, no matter who the mayor is, cities have utilized no-bid contracts to the tune of billions of dollars. Look, I’m a former small business owner. No small business owner would use no-bid contracts. You always competitively bid.”

These aren’t new Menin arguments(I would know). In a speech at the Association for a Better New York(ABNY) on February 4th, she laid out the same healthcare cost numbers and procurement reform agenda. And back in January, speaking to NY1, she had already signaled this approach, saying she’d spoken to the governor and that Hochul was “very, very clear that she is not willing to do anything on taxes.” Menin’s conclusion then: “We’ve got to identify savings in the budget.”

Menin’s position is politically significant in that she’s not calling for DOGE-style austerity, and she’s not saying cut social programs, as some people online are saying she is in Peter Sterne’s mentions. She’s saying the city is wasting billions of dollars through bad procurement and unchecked healthcare costs, and that those are the savings that should close the gap before anyone talks about raising taxes or cutting services, which, I mean, I hope she’s right, but I’m skeptical that finding waste alone will end up closing a 5.4 billion dollar hole without going to war with new york health insurance oligarchs, nor do I think that’s something she wants to do or will ever do.

Regarding all of this, the budgetary questions that will play out over the next four months are pretty simple if we’re being reductionist(which I am, this is my blog): does Albany tax the rich, does the city tax everyone else, or does Menin find enough waste so nobody has to make a choice? I genuinely don’t know, but I’d bet money (not $127 billion worth) that the answer ends up being some messy combination of all three, and, on a more selfish level, for the rent on my place, I hope it’s less so in the property tax direction.

For what happens next, the budget deadline is June 30th, and between now and then:

The City Council will hold preliminary budget hearings and release its own projections by April 1st.

The Comptroller’s office will release its full fiscal analysis on March 11th.

Agency Chief Savings Officers, created by Mamdani’s executive order, will release savings reports by March 20th.

The mayor will release a revised executive budget in late April.

Negotiation between City Hall, the Council, and Albany will play out through the spring.

AND: There’s a “Tax the Rich Rally” on February 25th in Albany.

Again, why did Menin give the most useful info for her stance on the Sid Rossenburg show? Like, he’s this guy?